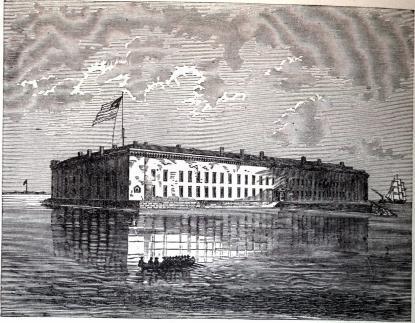

In April 1861, war clouds gathered over Charleston Harbor as Major Robert Anderson, commanding the United States garrison at Fort Sumter, waited to be resupplied or evacuated. Charleston Harbor had been heavily fortified by Confederate Brigadier-General Pierre Beauregard and he had been ordered by the Confederate War Department in Montgomery, Alabama, to allow no resupply of Sumter. Both men knew each other intimately, and had a long and close relationship. Robert Anderson had been Professor of Artillery at West Point, when Pierre Beauregard arrived as a sixteen year old cadet.

Anderson became Beauregard’s favorite professor and Beauregard became Anderson’s favorite student. After graduating second in his class at West Point in 1838, Beauregard chose to remain at West Point as Anderson’s assistant. Now twenty-three years later, they faced each other across Charleston Harbor on different sides of a looming conflict.

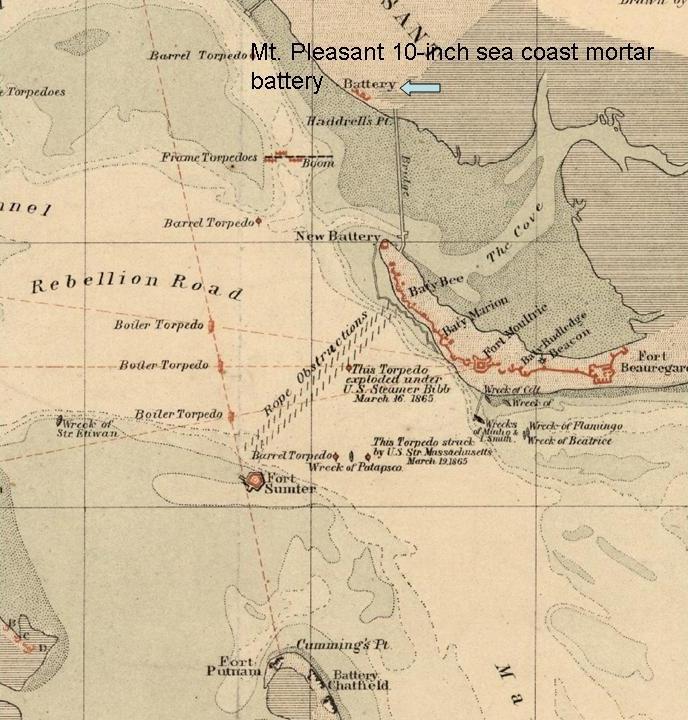

Tensions were high in the harbor as Confederate forces expected a Union fleet to appear at any moment with reinforcements and supplies for Anderson. The Union garrison at Sumter was running short of provisions and Sumter was surrounded by Confederate batteries. One of these batteries was a small sea-coast mortar battery in the village of Mount Pleasant. It contained two 10-inch sea-coast mortars and was commanded by Captain Robert Martin, South Carolina Militia. Here in early April 1861, America’s bloodiest war almost began a week early due to an incident with this Mount Pleasant battery.

On April 5th and again on the morning of April 6th, Captain Martin conducted live firing of his mortars and several of the Mount Pleasant battery’s shells exploded next to Fort Sumter spraying shrapnel dangerously around its walls. This was not the first time a Confederate shell had struck Fort Sumter. On March 8th, a battery on Morris Island accidentally fired a shell during practice, which hit the stone wharf at Fort Sumter. A sheepish South Carolinian, Major Stevens, rowed out to the fort and apologized for the incident. Anderson’s staff snickered as he chastised Major Stevens for the accidental shot that he warned could start a war. No one from the Mount Pleasant battery rowed out to apologize in April and Major Anderson and his staff did not laugh this one off.

Later in the afternoon, a note was delivered to General Beauregard from Major Anderson. He mentioned the dangerous firing by the Mount Pleasant mortar battery and suggested that the direction of its firing be changed. Anderson further added, “I hope, therefore, that, to guard against the possibility of such an event (one, I know, that you would never cease to regret), you will issue such orders as are proper in the case.” He used his personal connection with Beauregard as noted above with his comment on the possible consequences of the mortar fire which could lead to: “…one, I know, that you would never cease to regret.” It was a plea not to begin a war that was coming and Anderson knew it would pit brother against brother and favorite professor against favorite student. He ended his note to Beauregard with these words, “…I most earnestly hope that nothing will ever occur to alter, in the least, the high regard and esteem I have for so many years entertained for you.” It was the plea of a beloved professor to his beloved student.

The next morning, April 7th, Beauregard’s answer was rowed across Charleston Harbor to Anderson, stating, “I regret to learn that the firing from the mortar battery yesterday was so directed as to render the explosion of the shells dangerous to the occupants of Fort Sumter.” His regret was matched by his actions as he told Anderson that he would order Captain Martin to redirect the direction of his mortar practice from the Mount Pleasant battery. Beauregard also ended his letter as his favorite professor had by recalling their close relationship with the following words, “Let me assure you, major, that nothing shall be wanting on my part to preserve the friendly relations and impressions which have existed between us for so many years.” It was the answer of a beloved student to a beloved professor. Unfortunately, events would bring their years of being on the same side and serving the same nation to a tragic end, but the firing of the Mount Pleasant battery would not yet bring what fate had ordained to occur subsequently in five days time. T. S. Eliot has observed, “April is the cruelest month.”

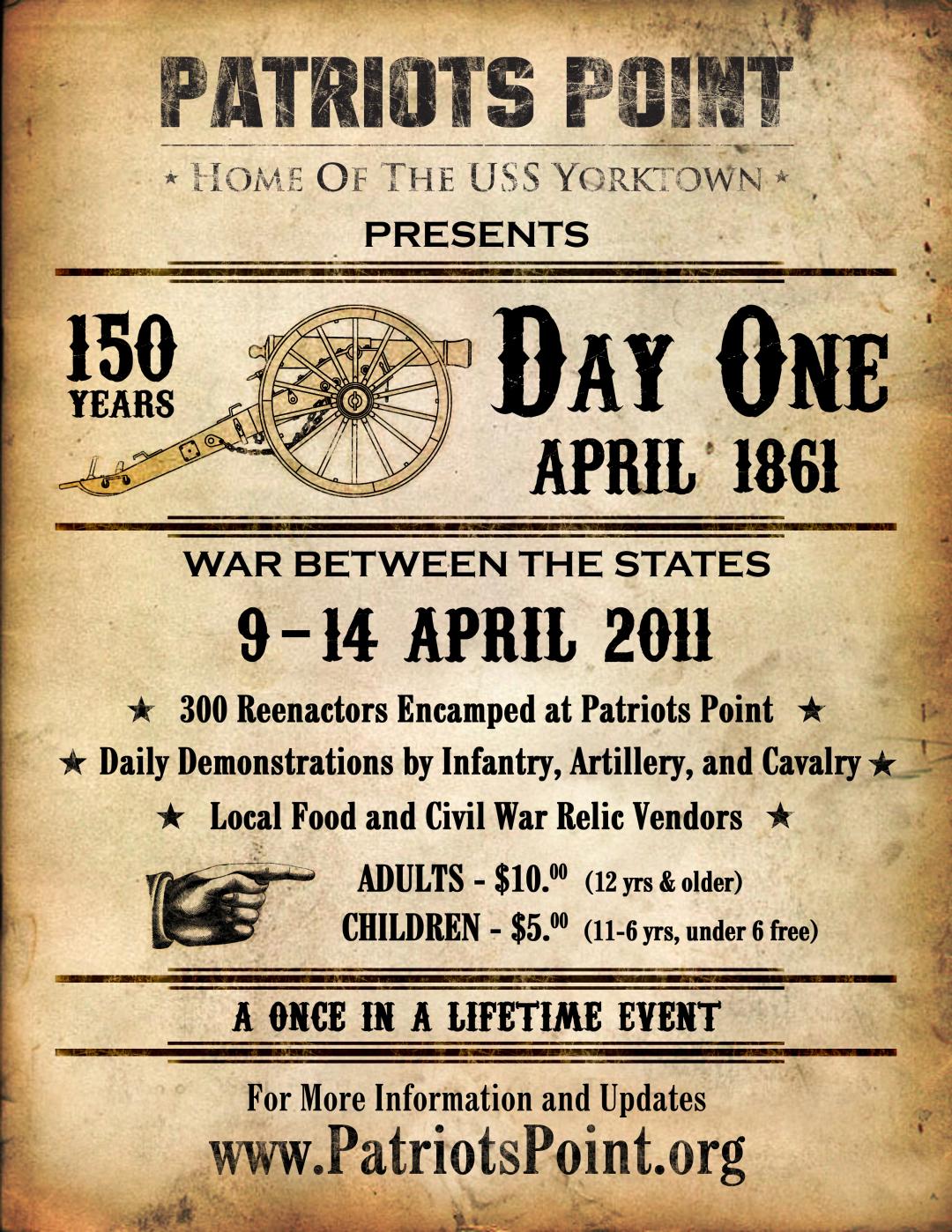

Beginning this Saturday, April ninth, the sounds of The War will return to Charleston Harbor and Mount Pleasant with events at Patriots Point’s “Day One: April 1861” Sesquicentennial program. Over 300 reenactors and approximately 24 artillery pieces will arrive to begin daily demonstrations to include living history programs covering civilian, medical, military and musical aspects of The War. They will be offered from Saturday, April 9th, through Thursday, April 14th. Special evening programs take place on Monday and Tuesday nights with artillery firing and music by the 97th Regimental Band. Tickets are $10 adult, $5 youth (11-6) and under 5 Free. Read more details at www.PatriotsPoint.org.